The Alhambra, the palace complex of the Nasrid dynasty in Granada, can perhaps be considered as one of the most famous examples of Islamic art overall, but is certainly the culmination and grand finale of medieval Islamic culture on the Iberian Peninsula. Our idea of the Alhambra is defined by the buildings of its apogee in the 14th century, which were constructed at the same time as York Minster, Cologne and Milan Cathedrals, the Strasbourg Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, the Pope’s Palace at Avignon, the Signorie of Florence and the town halls of Bruges and Prague.

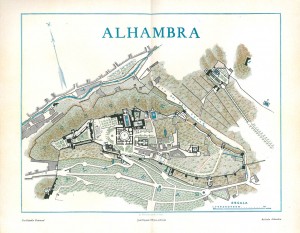

The history of the Alhambra building complex, however, stretches right back in Islamic times to the 9th century. We first learn of the existence of the “Red Fort” (for that is what al-hamra means) around 860, though nothing remains of this today. The earliest buildings of the Alhambra that can be dated are from the 11 th century, from the time of the Zirid dynasty, under which a forerunner of the Alcazaba came into being. The present area of the Alhambra, with its wall and its earliest towers in position, began to take shape under the Nasrids, the last Islamic sultanate on the Iberian Peninsula, in the first few decades of the 13th century. The dynasty had made the southern Spanish city of Granada the capital of its kingdom. For a long time, the sultanate was able to exist alongside the Christian rules by means of a skillful policy of treaties, vassalage, and military campaigns, while at the same time being adept at furthering its own cultural development. Construction of the Generalife, a summer palace near the Alhambra that underwent many alterations by subsequent sultans, probably started at the beginning of Nasrid rule. At the beginning of the 14th century, Muhammad III (1302-1309) contributed to the infrastructure of the city center, the Medina, with the construction of the mosque, the adjoining baths, the rauda(the sultans mausoleum), and the Puerta del Vino (“Wine Gate”), where the main street, the Calle Real, left the city. The actual palace area of the Nasrids was first developed under Ismail I (1314—1325). There are still significant remains of his palace, hidden among the palaces of the second half of the 14th century. The middle of the 14th century saw the sultanates most fertile period under Yusuf I (1333—1354). He built the Palacio de Comares (“Comares Palace”), the city gates of the Puerta de la Justicia (“Gate of Justice”) and the Puerta de los Siete Suelos (“Gate of the Seven Stories”), and, among other things, the wonderful Torre de la Cautiva (“Tower of the Captives”). The golden age of the Nasrid dynasty was undoubtedly that of Muhammad V in his second reign (1362-1391). The Riyad Palace also known as the Patio or Palacio de los Leones (“Court of the Lions” or “Palace of the Lions”) — owes its existence to him. In terms of architecture and wall decoration, this is one of the masterpieces of Islamic culture. The present appearance of the Alhambra is the work of Muhammad V, for it was in his reign that buildings were decorated and many more were erected. During the 15th century, the sultans time was increasingly taken up with the advancing Christian armies rather than artistic creativity. As a result, this was a period of decline, with no significant construction work and with no innovation in terms of building ornamentation. Before that, however, Muhammad VII (1392—1408) built the Torre de las Infantas (“Towers of the Infantas”) on the city wall, and Yusuf III (1408—1417) made alterations to the Generalife and built his own palace in the part of the palace area called the “Partal.” When the Christians captured the city at the end of the 15 th century, they reinforced the city wall and the major gateways with circular bastions, so that they could better withstand an artillery attack. The Christian governors made alterations primarily to the houses and the urban structure, adapting them to their own requirements. These works also affected the palaces, as the Patio de la Reja and the Patio de Lindaraja illustrate. The Palace of Charles V, a jewel of the European Renaissance, is the 16th century’s major contribution to the Alhambra, and represents a counterpoint to the Moorish buildings. Planned in 1526 as an imperial palace on the Alhambra, it was never actually completed. The Convento de San Francisco (“Monastery of St. Francis”), the beautiful Charles V fountain at the Puerta de la Justicia, and the Puerta de las Granadas (“Pomegranate Gate”) on the ascent to the palace complex, are also Renaissance contributions to the Alhambra. In 1576, the Friday Mosque was demolished and replaced by the Church of S. Marfa de la Alhambra, which was completed in 1617.

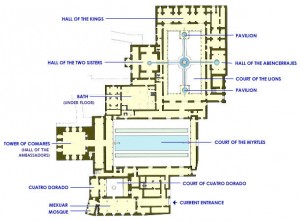

The palace complex

From a geographically favorable position on a high plateau, the Alhambra kept watch over the kingdoms capital city situated at its feet. It acted as the administrative and power center of Granada and as such is in line with the typical Islamic palace complex containing the sultans residence and seat of government. It developed following the municipal architectural ideas of medieval Islamic culture. It was laid out as an independent fortified town, separate from Granada, its medina and suburbs, with a city wall approximately 1,900 yards (1,730 meters) long, which had about 30 towers, varying in size and function. Granada and the Alhambra were two cities that complemented each other, but were autonomous, and their sole point of direct contact was at the Puerta de las Armas (“Arms Gate”). This gateway, which was situated between the Albaidn — the town district on the hill opposite the Alhambra — and the lower city, represented the most important connection between the two. Through it the subjects entered the palace complex to seek an audience with the court, to sort out administrative matters, to pay dues, or to undertake other such tasks. Gradually, and especially after the last few decades of the 15th century, the population of Granada increased considerably due to the arrival of Muslim refugees from other cities conquered by the Christian armies. This created a new town area with its own walls, which in the end almost surrounded the Alhambra.

Puerta de la Justicia. Built in 1348 by Sultan Yusuf I, the Gate of Justice is the largest of the Alhambra’s four outer gates. A hand is carved in the keystone of the outer horseshoe arch, which, like the key in the inner arch, is one of the symbols used by the Nasrids in facade decoration. The large foundation inscription is above the entrance, to which, in the 16th century, the Christian kings added a statue of the Virgin Mary by Roberto Aleman. The vaults inside the gate, which has to negotiate a great difference in height are lavishly painted.

The Wine Gate was one of the first gates erected in the inner area of the Alhambra. Built between 1303 and 1309, it was the entrance to the Medina, the area of town within the fortress where the administrative and court officials lived. The Puerta del Vino had a dual protective function, in that its strong doors could be locked to protect against attack from enemies outside the city and also if the inhabitants of the Medina rose up against the sultan. Despite its function as a fortification, the gate looks like a public pavilion.

The Alcazaba

The Alcazaba

From the terrace of the Torre de la Vela, there is a fine view over the inner area of the Alcazaba. The remains of the foundation walls still give an impression of this small quarter, which contained the homes and barracks of the guard. Depending on size, the two-story houses had one to three rooms on each floor. The public facilities included a steam bath, cistern, and communal kitchen. As you would expect for a military district, there were also prisons – underground rooms accessible only by ladders or ropes.

The royal palaces

The Alhambra is held in such high esteem primarily because of the Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions, both dating from the 14th century. Since the 16th century, these two buildings together have been called the Casa Real Vieja (“Old Royal Palace”), to distinguish them from the large Renaissance palace of Emperor Charles V, the Casa Real Nueva (“New Royal Palace”), built at that time. The Catholic Monarchs retained the medieval Nasrid palaces as private residences to enjoy their magnificent decor and as they stipulated in their will, “so that they may never be forgotten.” Although partly altered in shape, neglected, sacked, and left to the mercy of nature over the centuries, most of their structure and decoration have survived.

Main facade of the Comares Palace.In 1370, Muhammad V commissioned the decoration of the Comares Palace facade, which faced the Cuarto Dorado.The door to the right gave access to the private apartments of the palace, while the ones to the left led to the official halls of the Comares complex. An inscription over the doorways reading “My gateway is a fork in the ways” summarizes this arrangement. A projecting roof that used to be painted in bright colors deserves special mention, as it is a gem of Islamic carpentry.

Court of the Myrtles in the Comares Palace. The Comares Palace, built under Yusuf I, is in line with typical Nasrid building design, with all the important rooms arranged around a splendid inner courtyard. The residential apartments are on the long sides of the Court of the Myrtles, while at each narrow end a portico leads onto the public reception and administrative halls. In the background rises the Torre de Comares, the highest tower of the Alhambra, which houses the Throne Room.

The most elegant apartments, most of which were in the northern part, were lit from the south. These rooms also occasionally open onto the north. In the Alhambra palaces, this occurred where the steep slope of the hill offered them some protection.

Detail of the central arch of the portico on the northern side of the Court of the Myrtles. Behind the richly decorated arch of the portico you can see the beautiful muqarnas arch, immediately in front of the entrance to the throne room. It is decorated throughout in carved stucco, originally painted in many colors. The arches are purely decorative and have no supporting function.

Detail of an inscription. As well as various other decorative elements, all

the palace rooms display a large number of epigraphic embellishments, mostly poems or qasidas that refer to the place or to the sultan who commissioned the construction work. Other writings praise and glorify Allah, or quote from the Koran.

Palacio de los Leonas. Apart from the Comares Palace, the Palace of

the Lions is the only palace in the Alhambra to have survived from the 14th century. It is made up of a system of separate private residential areas, grouped around a patio. The famous Court of the Lions is bordered on all sides by a gallery of columns, with the individual apartments behind. The whole courtyard area is intersected by four water channels in the shape of a cross, alluding to the points of the compass, and fed by the fountain in the

center of the courtyard.

The fountain in the Court of the Lions. Even in the 14th century, a complex hydraulic system provided sufficient water pressure and a constant water level in the fountain. The 12 lions, from whose jaws the water flows down, symbolize all 12 signs of the zodiac and thus the entirety of time, eternity. Verses written by the vizier and poet Ibn Zamrak adorn the dodecagonal rim of the fountain.

Capital of columns in the Court of the Lions. The slender marble columns of the galleries that surround the courtyard are particularly impressive. The symmetrical, cube-shaped capitals, with their moldings decorated with inscriptions praising the architect Sultan Muhammad V, deserve particular attention.

The portal pavilion in the Court of the Lions. The geometric design of the architecture of the Court of the Lions is particularly emphasized by the two square-shaped pavilions that project into the east and west axis of the courtyard.The architecture of the Alhambra is distinctive for the ephemeral nature of the materials used: as most of the columns and arches are purely decorative and have no supporting function, they could be made of soft stone and plaster. The masterly arrangement of projections and recesses, the modulation of exterior surfaces, and the gradation of richly decorated muqarnas arches help to create the particular aesthetic effects of the Alhambra with the play of light and shadow.

Hall of the Kings. The Sala de los Reyes is an elongated chamber, divided into several rooms by a series of muqarnas arches. The alcoves in the back wall give an unrestricted view onto the courtyard. The three alcoves that open onto the Sala de los Reyes have vaults that are among the Alhambra’s most important decorative treasures.

The Partal (or Portico) Palace is the oldest palace in the Alhambra. It was probably built at the beginning of the 14th century, but all that remains from its original form are the large central pool and the five-arched portico that gave the palace its name.

The maze garden between the Alhambra

and the Generalife

Interior view of the Torre de las Infantas. Roughly 30 towers of varying size and shape punctuate the outer wall of the Alhambra. In addition to the towers, which are an integral part of specific palaces, there are also so called palace towers, which differ from the others in their decor and building features. The Torre de las Infantas was built between 1392 and 1408, and comprises a roofed courtyard with various alcoves and adjoining apartments, which are arranged around it creating two stories.

The Generalife

Palace of the Generalife. The Generalife includes not only seven vegetable gardens but also an elegant palace, similar to the Alhambra palaces in terms of construction and decoration. Here, too, an elongated patio with a water source forms the focal point around which the palace was built. Instead of the usual fountain, the Generalife has a canal, known as the Acequia, sur-rounded by gardens that gave the courtyard its name. Here, too, the ingenious hydrotechnology provides convincing evidence of the great significance and symbolism of water throughout Islamic cultures.

The Nasrid sultans also had many estates to provide for them or where they could build outside the city walls of the Alhambra. Some of these lay in the area surrounding the palace district. By far the best preserved is the Generalife(jannat al-arifa), which is directly adjacent. In contrast to the past, the Generalife is now linked to the Alhambra by a series of gardens created in the first three decades of the 20th century and based on a free interpretation of the Spanish-Muslim garden. The “jannat prefix means “the gardens” in the comprehensive sense of the word as a place of vegetation, of cultivation. Surrounded by almost 500 acres (220 hectares) of meadowland, the four large vegetable gardens form the Generalife, which is dominated by a palace building with ornamental gardens. Most of the vegetable gardens are still cultivated today and so the site of the Generalife is also of major ecological and even anthropological, not just historical, significance.

The central building in the Generalife displays the same architectonic structure as the Alhambra palaces: a patio with a water source — in this case part of the canal that used to irrigate the estate by means of four watercourses forms the central point of the residential buildings. The most elegant room lies on the northern side and opens onto the countryside via a mirador; or observation tower. The patio has coordinate axes inlaid with four large, lower-lying beds on the edge of the water channel, which is bordered by narrow paths. Despite the decidedly rural nature of this complex, which is particularly striking in the entrance courtyards, the building is decorated like a palace. It is embellished throughout with alicatado dadoes, stucco panels that covered the walls right up to the timber ceilings and roof struts, geometric decor, calligraphy, muqarnasand atauriques, marble columns, arches, and latticework, etc. The smallmirador projecting from the patio is particularly remarkable with its magnificent view over the vegetable gardens and the Alhambra behind.

The cityscape of Granada

Through many openings in the walls, windows, and open loggias, especially in the magnificent halls of the Alhambra, there is an unrestricted view direcdy onto the town of Granada situated at the foot of the hill.

Patio de la Sultana, in the Generalife. Although the medieval structure of the

Generalife has for the most part survived, it has seen some changes over the centuries. Thus the baroque garden, for example, was laid out where the palace baths used to be. The garden with its many ornamental water fountains is now called the Patio de la Sultana.