ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2015 Regional Conference of the World Association of Public Opinion Research (WAPOR) in Doha, Qatar. Bethany Lynn Nesbit, Post-Doctoral Fellow at Qatar University’s Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI), presented “When Do Women Care? Exploring the Gender Gap in Political Interest in Qatar” as part of the session “Family and Gender” on Monday, March 9th, 2015.

Post developed by Bethany Nesbit (Shockley).

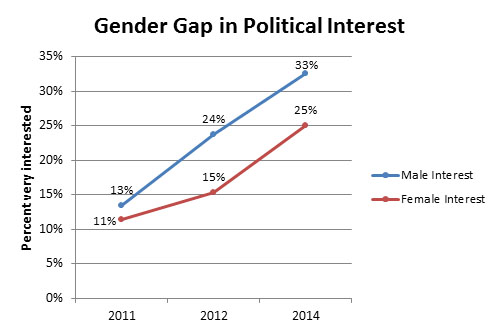

Interest in politics is often considered to be the root of political participation and engagement. Citizens who care about politics are more likely to get involved in making their country a better place. Recent trends show that interest in politics has increased among Qataris between 2011 and 2014. However, females lagged behind males in their levels of political interest in 2012 and 2014. What could be driving this divergence in political concern?

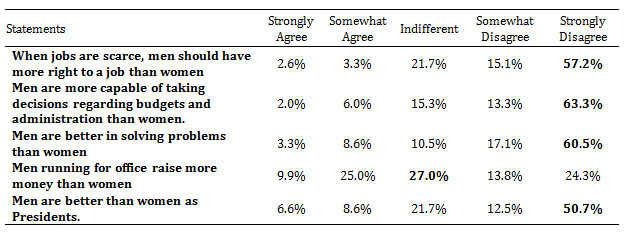

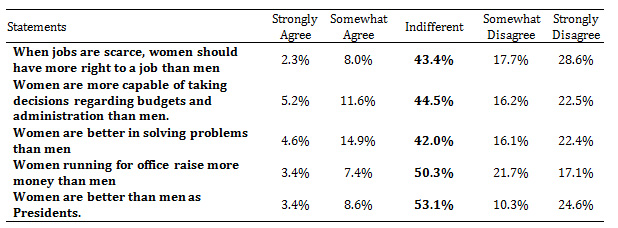

In my paper, I investigate several potential explanations for the gender gap, including socio-economic factors such as income, education, and age. I also examine the role of cultural and religious influences, including attitudes about gender roles in order to explain interest in politics. These are causes that have been shown to be important predictors of political interest in industrialized Western democracies, but have not been tested in the Qatari context. Qatar, a rapidly-developing country located in the Arabian Peninsula, is rich in hydrocarbon resources and governed by a hereditary Emir.

In my paper, I investigate several potential explanations for the gender gap, including socio-economic factors such as income, education, and age. I also examine the role of cultural and religious influences, including attitudes about gender roles in order to explain interest in politics. These are causes that have been shown to be important predictors of political interest in industrialized Western democracies, but have not been tested in the Qatari context. Qatar, a rapidly-developing country located in the Arabian Peninsula, is rich in hydrocarbon resources and governed by a hereditary Emir.

Using data from the SESRI Omnibus surveys in 2011, 2012, and 2014, I test the role of socio-economic factors against other cultural and behavioral factors. In doing so, I find strong support for two particular predictors of political interest – education and social media usage – although age and income were also significant predictors in 2011. Education increases interest in politics considerably. Social media usage has a less dramatic impact, but it is especially important for young Qataris, who engage with it far more frequently than their older counterparts.

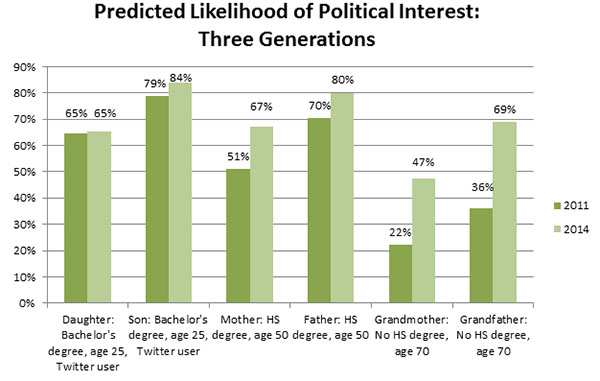

In order to illustrate the impact of these variables at two different time periods, 2011 and 2014, I use simulations to produce predicted probabilities of being interested in politics. In the figure below, 100% means that this person is certainly interested in politics, while 0% corresponds to someone who is certainly NOT interested in politics, and a 50% likelihood of being interested means that the person could go either way.

The figure above simulates the likelihood that hypothetical people with particular characteristics will be interested in politics. The example illustrates a family in which the son and daughter (who are the same age) are both holders of bachelor’s degrees, while their less educated, but older parents, have a high school education. Imagine that this hypothetical family also has a set of grandparents who did not finish high school. The young university graduates are also Twitter users, while their older relatives are not.

The figure above simulates the likelihood that hypothetical people with particular characteristics will be interested in politics. The example illustrates a family in which the son and daughter (who are the same age) are both holders of bachelor’s degrees, while their less educated, but older parents, have a high school education. Imagine that this hypothetical family also has a set of grandparents who did not finish high school. The young university graduates are also Twitter users, while their older relatives are not.

The figure shows that education can greatly increase the likelihood of interest, as the college educated daughter is much more likely to be interested in politics than her less educated grandmother. However, we see that gender gaps persist over time, especially among the younger generation (illustrated by the son and daughter). Interest in politics did not increase at all for the daughter between 2011 and 2014, though both the grandmother and the mother made significant gains during this time. This suggests that education can give women the tools they need to engage with issues in society, but it alone cannot close the gender gap in political interest. Instead, other engagement strategies such as social media campaigns may capture young women’s attention.