ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2015 Regional Conference of the World Association of Public Opinion Research (WAPOR) in Doha, Qatar. Justin Gengler, Research Projects Manager in the Policy Unit team at Qatar University’s Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI), presented “Interviewer Effects in the Arab World: Evidence from Qatar” as part of the session “Data Collection” on Monday, March 9th, 2015.

Post developed by Justin Gengler.

My paper, which examines the issue of interviewer effects in surveys conducted in Qatar, is the first output from a long-term research project conceived shortly after my arrival at SESRI in late 2011. Having then recently finished a mass political survey of Bahrain in which interviewer characteristics played an influential role in shaping survey responses across an array of substantive topics, I was surprised to discover that not all of SESRI’s interviewers at that time were non-nationals. However, this may not seem surprising when one considers the economic and social disincentives for nationals to work as field interviewers.

To test whether what I observed in Bahrain would also hold true for Qatari respondents, my collaborators and I designed a survey experiment that enabled us to isolate and measure the influence of interviewers being either Qatari or non-Qatari in nationality. In order to do so, we had to recruit Qatari nationals to conduct the interviews, and for this we turned to Qatar University students.

We were able to recruit approximately 45 female student interviewers (as we wanted to remove the impact of interviewer gender, males were excluded). We were pleased to be able to recruit 31 interviewers who were of Qatari nationality, as well as 14 non-national interviewers who spoke Egyptian, Levantine, and North African Arabic dialects. All 45 interviewers underwent standard field interviewer training together, and the students were enthusiastic about the project.

Survey respondents were randomly assigned to either the Qatari or non-Qatari interviewer group, and this group assignment was preserved even in the case of callback, dropped calls, or other eventuality. During a few weeks of interviewing in June 2014, we reached a total of 1,587 respondents, 1,288 of whom completed the entire survey. Of these, 832 of the surveys (53%) were carried out by Qatari interviewers.

As expected, we found that Qatari respondent answers differed based on whether they were being interviewed by a Qatari. But in addition, we also found that Qatari interviewers tended to recruit and retain different types of Qatari respondents than the non-Qatari interviewers. Qatari interviewers recruited on average more males, and respondents who were slightly older and had lower levels of education.

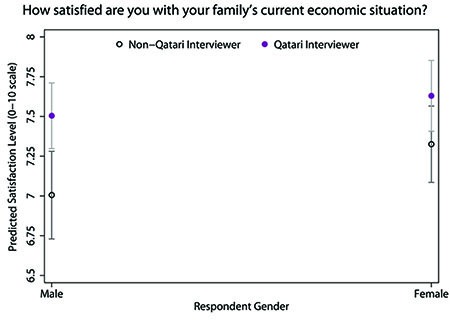

Even after accounting for the different types of Qatari respondents interviewed by Qataris and non-Qataris, interviewer nationality still exerts an important influence over Qataris’ responses. Two topics in particular seem especially sensitive to interviewer nationality:

1. On self-assessments of respondents’ economic/financial situations, Qatari respondents tend to give more positive economic self-assessments when asked by Qatari interviewers.

2. On attitudes toward foreigners and policies related to immigration and naturalization, Qatari respondents tend to give answers to Qatari interviewers that are more negative than the answers given to non-Qatari interviewers.

2. On attitudes toward foreigners and policies related to immigration and naturalization, Qatari respondents tend to give answers to Qatari interviewers that are more negative than the answers given to non-Qatari interviewers.

We did find that answers on some topics did not differ between Qatari and non-Qatari interviewers. In particular, we found that answers to items about political interest and attitudes and voting behavior —items that are likely to evoke sensitivities but do not otherwise carry local social or economic connotations— were not impacted by the nationality of the interviewer. This suggests that interviewer effects in Qatar do not stem from a greater trust in or comfort level with Qatari interviewers per se, but rather from an in-group/out-group dynamic rooted in the distinctive demographic character of Qatar and similarly-configured Arab Gulf states.