About the Author

-

Louis Wirth was an American sociologist and member of the Chicago school of sociology.

-

Born: August 28, 1897,Germany

-

Died: May 3, 1952, NY.US

-

Education: University of Chicago

-

Books: The Ghetto

Louis Wirth proposes a new academic paradigm for city life as sociological construct. Lacking a suitable set of hypotheses, scholars would benefit from a more comprehensive portfolio of city characteristics, ultimately moving the field towards a theoretically informed notion of urbanism. Grafting sociological propositions onto urbanism research, Wirth details three empirical areas of focus: population size, density, and demographic heterogeneity.

A Sociological Definition of the City

. . . Geographers, historians, economists, and political scientists have incorporated the points of view of their respective disciplines into diverse definitions of the city. . . . A sociologically significant definition of the city seeks to select those elements of urbanism which mark it as a distinctive mode of human group life. The characterization of a community as urban on the basis of size alone is obviously arbitrary. No definition of urbanism can hope to be completely satisfying as long as numbers are regarded as the sole criterion.

A sociological definition must obviously be inclusive enough to comprise whatever essential characteristics . . . different types of cities have in common as social entities. we may expect the outstanding features of the urban-social scene to vary in accordance with size, density, and differences in the functional type of cities.

For sociological purposes a city may be defined as a relatively large, dense, and permanent settlement of socially heterogeneous individuals.

III A Theory of Urbanism . . .

On the basis of the postulates which this minimal definition suggests, a theory of urbanism may be formulated in the light of existing knowledge concerning social groups.

The larger, the more densely populated, and the more heterogeneous a community, the more accentuated the characteristics associated with urbanism will be. . . .There are a number of sociological propositions concerning the relationship between (a) numbers of population, (b) density of settlement, (c) heterogeneity of inhabitants and group life.

a) Size of the Population Aggregate

Large numbers involve a greater range of individual variation. . . .

That such variation should give rise to the spatial segregation of individuals according to color, ethnic heritage, economic and social status, tastes and preferences, may readily be inferred. The bonds of kinship, of neighborliness, and the sentiments arising out of living together for generations under a common folk tradition are likely to be absent or, at best, relatively weak in an aggregate the members of which have such diverse origins and backgrounds. Under such circumstances competition and formal control substitutes for the bonds of solidarity that are relied upon to hold a folk society together. . . .

Characteristically, urbanites meet one another in highly segmental roles. They are, to be sure, dependent upon more people for the satisfaction of their life-needs than are rural people and thus are associated with a greater number of organized groups, but they are less dependent upon particular persons, and their dependence upon others is confined to a highly fractionalized aspect of the other’s round of activity. This is essentially that is meant by saying that the city is characterized by secondary rather than primary contacts. The contacts of the city may indeed be face to face, but they are nevertheless impersonal, superficial, transitory, and segmental. The reserve, the indifference, and the blasé outlook which urbanites manifest in their relationships may thus be regarded as devices for immunizing themselves against the personal claims and expectations of others.

The superficiality of urban-social relations results in the sophistication and the rationality generally ascribed to city-dwellers. Our acquaintances tend to stand in a relationship of utility to us in the sense that the role which each one plays in our life is overwhelmingly regarded as a means for the achievement of our own ends. Whereas, therefore, the individual gains, on the one hand, a certain degree freedom from the personal and emotional controls of intimate groups.

In a community composed of a larger number of individuals than can know one another intimately and can be assembled in one spot, it becomes necessary to communicate through indirect mediums and to articulate individual interests by a process of delegation.

A number of population occupying a specific area in a district

Density . . .

In the case of human societies, an increase in numbers when area is held constant tends to produce differentiation and specialization, since only in this way can the area support increased numbers. Density thus reinforces the effect of numbers in diversifying men and their activities and in increasing the complexity of the social structure.

Typically, our physical contacts are close but our social contacts are distant. The urban world puts a premium on visual recognition. We see the uniform which denotes the role of the functionaries and are oblivious to the personal eccentricities that are hidden behind the uniform.

Density, land values, rentals, accessibility, healthfulness, prestige, aesthetic consideration, absence of nuisances such as noise, smoke, and dirt determine the desirability of various areas of the city as places of settlement for different sections of the population. Place and nature of work, income, racial and ethnic characteristics, social status, custom, habit, taste, preference, and prejudice are among the significant factors in accordance with which the urban population is selected and distributed into more or less distinct settlements. Diverse population elements inhabiting a compact settlement thus tend to become segregated from one another in the degree in which their requirements and modes of life are incompatible with one another and in the measure in which they are antagonistic to one another. Similarly, persons of homogeneous status and needs unwittingly drift into, consciously select, or are forced by circumstances into, the same area.

The different parts of the city thus acquire specialized functions. The city consequently tends to resemble a mosaic of social worlds in which the transition from one to the other is abrupt. The juxtaposition of divergent personalities and modes of life tends to produce a relativistic perspective and a sense of toleration of differences which may be regarded as prerequisites for rationality and which lead toward the secularization of life.

The close living together and working together of individuals who have no sentimental and emotional ties foster a spirit of competition. To counteract irresponsibility and potential disorder, formal controls tend to be resorted to.

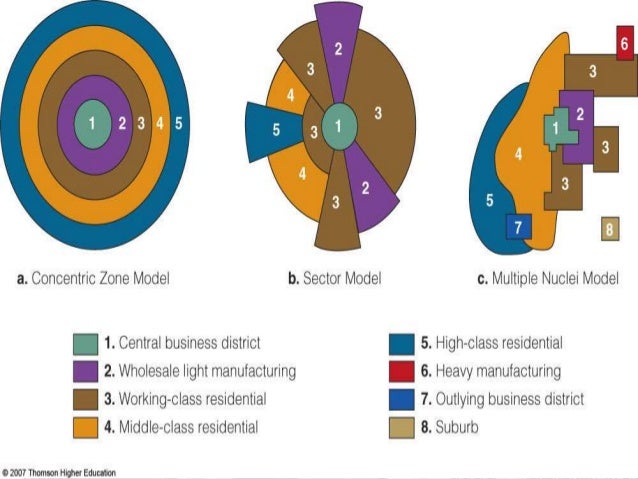

This diagram is an example of how the zones or the density of people and spaces are distributed in an area or a city.

Heterogeneity

The social interaction among such a variety of personality types in the urban milieu tends to break down the rigidity of caste lines and to complicate the class structure, and thus induces a more ramified and differentiated framework of social stratification than is found in more integrated societies. The heightened mobility of the individual, which brings him within the range of stimulation by a great number of diverse individuals and subjects him to fluctuating status in the differentiated social groups that compose the social structure of the city, tends toward the acceptance of instability and insecurity in the world at large as a norm. This fact helps to account, too, for the sophistication and cosmopolitanism of the urbanite. No single group has the undivided allegiance of the individual. . . . By virtue of his different interests arising out of different aspects of social life, the individual acquires membership in widely divergent groups, each of which functions only with reference to a single segment of his personality. . .

Although the city, through the recruitment of variant types to perform its diverse tasks and the accentuation of their uniqueness through competition and the premium upon eccentricity, novelty, efficient performance, and inventiveness, produces a highly differentiated population, it also exercises a leveling influence. Wherever large numbers of differently constituted individuals congregate, the process of depersonalization also enters. . . . The services of the public utilities, of the recreational, educational, and cultural institutions must be adjusted to mass requirements. Similarly, the cultural institutions, such as the schools, the movies, the radio, and the newspapers, by virtue of their mass clientele, must necessarily operate as leveling influences. The political process as it appears in urban life could not be understood without taking account of the mass appeals made through modern propaganda techniques. If the individual would participate at all in the social, political, and economic life of the city, he must subordinate some of his individuality to the demands of the larger community and in that measure immerse himself in mass movements. . . .

Urbanism in Ecological Perspective . . . .

Many of the technical facilities and the skills and organizations to which urban life gives rise can grow and prosper only in cities where the demand is sufficiently great. The nature and scope of the services rendered by these organizations and institutions and the advantage which they enjoy over the less developed facilities of smaller towns enhances the dominance of the city and the dependence of ever wider regions upon the central metropolis. . . .

One major characteristic of the urban-dweller is his dissimilarity from his fellows. Never before have such large masses of people of diverse traits as we find in our cities been thrown together into such close physical contact as in the great cities of America. . .

Ecological Urbanism

Urbanism As a Form of Social Organization . . . .

Being reduced to a stage of virtual impotence as an individual, the urbanite is bound to exert himself by joining with others of similar interest into organized groups to obtain his ends. This results in the enormous multiplication of voluntary organizations directed toward as great a variety of objectives as there are human needs and interests. While on the one hand the traditional ties of human association are weakened, urban existence involves a much greater degree of interdependence between man and man and a more complicated, fragile, and volatile form of mutual interrelations over many phases of which the individual as such can exert scarcely any control. Frequently there is only the most tenuous relationship between the economic position or other basic factors that determine the individual’s existence in the urban world and the voluntary groups with which he is affiliated. . . .

Urban Personality and Collective Behavior

Since for most group purposes it is impossible in the city to appeal individually to the large number of discrete and differentiated individuals, and since it is only through the organizations to which men belong that their interests and resources can be enlisted for a collective cause, it may be inferred that social control in the city should typically proceed through formally organized groups. It follows, too, that the masses of men in the city are subject to manipulation by symbols and stereotypes managed by individuals working from afar or operating invisibly behind the scenes through their control of the instruments of communication. Self-government either in the economic, the political, or the cultural realm is under these circumstances reduced to a mere figure of speech or, at best, is subject to the unstable equilibrium of pressure groups. In view of the ineffectiveness of actual kinship ties we create fictional kinship groups.[3] In the face of the disappearance of the territorial unit as a basis of social solidarity we create interest units. Meanwhile the city as a community resolves itself into a series of tenuous segmental relationships superimposed upon a territorial base with a definite center but without a definite periphery and upon a division of labor which far transcends the immediate locality and is world-wide in scope. . . .

It is obviously, therefore, to the emerging trends in the communication system and to the production and distribution technology that has come into existence with modern civilization that we must look for the symptoms which will indicate the probable future development of urbanism as a mode of social life. . . .

Relation to Qatar

Urbanism as away of life in Qatar in terms of a) numbers of population, (b) density of settlement, (c) heterogeneity of inhabitants

Number of population:

Qatar has witnessed unprecedented economic and population growth, at a rate not seen Anywhere else, Qatar had the world’s fastest growing population, Qatar population Growth more than double since 1950- 2000, where it held the place of the world’s 2nd Fast growing population, from 2000-2010 Qatar is 1st with 10.91% growth and in 1950-2000 Qatar is 2nd with 6.29% this rapid growth has exerted pressure on Qatar’s Transportation systems, traffic, the concentration of the residence is in Doha city mainly due to the concentration of the facilities in it.

The country is now in a period of transportation and planning redesign and expansion to meet the needs of the rapidly growing population. Not to forget that Qatar is one of the gulf cities therefore it has got different people of different cultural background, ethnic heritage, origins. Therefore, in Qatar there are huge segregation between people in workplaces, in professions, and etc….

Density . . .

In the case of human societies, an increase in numbers when area is held constant tends to produce differentiation and specialization. Density thus reinforces the effect of numbers in diversifying men and their activities and in increasing the complexity of the social structure.

Density and heterogeneity in Qatar

Most of the population are male’s, while Qatari population continues to be a balanced Population, with male-female gender ratio of 98.7 males per 100 females in 2010, The gender ratio of non Qatari population is 398.1 males per 100 females. As a result Of the large male-non Qatari population, Qatar’s total population has a ratio of 310 males Per 100 females. The gender imbalance of Qatar’s total population also with including all the expats creates unique population needs, such as: accessibility, rentals, social status, and etc….

In terms of accessibility: public spaces, governmental organization, recreational spaces are concentrated in Doha because the other areas such as Dukhan, Al wakra, Al khoor , these areas don’t have much Facilities. Also regarding the public academic organization for universities, there is only one public university which is Qatar University located in Doha as well. However Qatar is currently undergoing an expansion process of their facilities

In terms of health fullness; Qatar’s total population creates unique population health needs , given the money gender-specific health differences , including health seeking behavior , and disease burden .

In terms of Rentals: Houses, apartments, villas, were sufficient and at affordable prices, however with the rapid ongoing process a large number of accommodations are getting built but due to the increase in the need there is an increase in the price of these houses, that then rely up on the social status and how much one is able to pay. Which will result in the ongoing segregation of people.

Heterogeneity with in the density

In terms of social status, in Qatar Diverse population elements inhabiting a compact settlement thus tend to become segregated from one another in the degree in which their requirements and modes of life are incompatible with one another . Similarly, persons of homogeneous status are forced by circumstances into, the same area. In Qatar, expats of mid status tend to live in stand alone villas or in compounds where each family is surrounded by other families of a fairly more or less homogeneous status. When it comes to the Qatari population they tend to live in what they call their own Fared, they live in private stand alone villas, but also it needs to be a private settlement or neighborhood where the tree of the family lives next to each others in the same Fared but in different villas.

However, in a work place to take an example like a contracting company, there will be the project manager who is a Qatari or an expat, the engineers, the client who is a Qatari in most of the cases, therefore, in work places in Qatar the social status will have some variations as well as segregation of roles and status.

Qatar’s map with the different cities, showing Doha marked in a red square, this map identifies the future expansion that is currently going on as the country has a sufficient land however, it need to be modified and re designed to meet the needs of the rapidly growing populations

Conclusion

Communication and contacts between people in the previous examples such as a compound or a facility or a public space or a work place, also varies. However, people’s physical contacts are close but their relation to each other is weak or it’s just based on relying on some one to get a particular task done.

References :

LeGates, R. (1996). The city reader. London: Routledge.

Written by: Dina Saleh